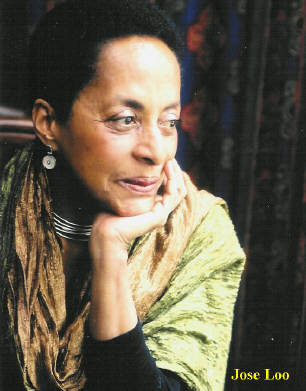

It was in 2010 when I posed a question about the world-class Afro-Peruvian singer Susana Baca in my blog post entitled, A Question about Susana Baca, who by the way, was the first Black cabinet minister of the Peruvian government.

It was in 2010 when I posed a question about the world-class Afro-Peruvian singer Susana Baca in my blog post entitled, A Question about Susana Baca, who by the way, was the first Black cabinet minister of the Peruvian government. To me, she is the Spanish-speaking version of Billie Holiday or Bessie Smith with upbeat rhythm sections along with fluid dance moves as she combines Afro-Peruvian, Afro-Cuban, and jazz in her music.

As I stated in my prior blog article, I was on a natural high for six months, after seeing her perform for the first time in 1999. This experience inspired several future trips to Perú where I established solid Afro-Peruvian social connections.

With all that said, here is my issue with Susana Baca:

She travels the world singing about Perú's

“African” culture, but seldom hires black Peruvian musicians in her

five-to-six-piece bands. I've seen her perform on three occasions and saw only one black

person in only one of those three performances. With black Peruvians suffering enough racial discrimination when it

comes to jobs, why is she perpetuating it through Afro-Peruvian music? Several people responded to my blog article mostly in agreement with my concern. Others wanted to withhold any judgement until they get more facts on the matter.

Finally, after three years, I get to hear some facts from Timothy, an African-American friend living in Perú with his Afro-Peruvian wife. He says that the US visa system is partly to blame. He explains that it is tough for Afro-Peruvians to get a visa because many are below the poverty level, and that Susana has to redo her entourage for each country with visa restrictions. Timothy added that there have been issues with members of her band who paid $1000s for an entertainment visa to a foreign country and later defected. The visa requirements for the US alone is set far above the income levels of Afro-Peruvians. Some need to own property to assure that they have a reason to return to Perú.