This blog is about my exposure to the Spanish language and various Latin-American cultures through travel and research; particularly Black/Afro-Latino.

Tuesday, May 28, 2013

My Work with Illegal Aliens

Undocumented immigrants (or illegal aliens) in the US are very diverse, and do not solely consist of Latin American people as so many of us are led to believe. There are people from Canada, Asia, Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Islands who are in this country without papers, thus the original meaning of WOP, which was directed at Italian immigrants who at one time were stereotyped as being without papers.

Many of such immigrants go unnoticed by authorities because they are not Latino. Jaime, a Peruvian friend, also goes unnoticed by immigration because he is “Afro” Peruvian and does not fit the stereotypical profile of a Latino. I never knew that a girlfriend who comes from a West African country was also undocumented until she started pressuring me to marry her for a green card. She even offered me a measly $6K to take her up on this charade.

In San Francisco, one of the many sanctuary cities for undocumented immigrants, where social service agencies not only made a commitment to protect these immigrants from the US Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE), but to also provide them with various services, such as housing, food, and employment assistance. One such company hired me to assist all of their marginalized clients, most of whom are on some type of public assistance, with jobs and careers. However, the undocumented immigrant clients presented big challenge.

These immigrants were five times more motivated to find employment than the American-born clients. The illegals seldom displayed any of the flakiness I so often experienced from the others who were often no-shows for appointments. On one occasion, I organized a job search workshop, and bought coffee, pizza, and other refreshments, and no one showed. I ended up feeding to the rest of the staff. When the time came to give workshops in Spanish, however, I had a full house of participants, and this full house primarily consisted of undocumented immigrants.

Many of them found jobs paying under-the-table, and others became successful in building their own businesses. Silvia, from Brazil who speaks limited English, but fluent in Spanish and Portuguese, developed a successful housekeeping service where I helped with the marketing. Her last words as she hugged and saw me for the last time were, gracias por todo (thank you for everything)!

Friday, May 24, 2013

My Spanish and My Job Search

Recently, my contract with a career development company working as a professional résumé writer ended, and I've been going on interviews for jobs where I can assist other job seekers as a counselor and/or a workshop instructor. Because I have such a passion for the Spanish language, one of my favorite job search strategies is to market my Spanish-speaking ability to companies that need Spanish speakers without saying that I'm bilingual or fluent.. Many employers confuse my ability to communicate in Spanish with fluency, and the employers who do speak Spanish often ask me questions in Spanish during interviews to get a real sense of my command of the language.

One day while working as an educational-vocational specialist at a social services agency in San Francisco, my supervisor who needed an interpreter, quickly ran over to my office for help. Several weeks later, this same supervisor remarked that I'm fluent. LOL—wrong! The Spanish-speaker whom I was able to help was simply satisfied to get the information he needed from my supervisor and could care less about my fluency and lack thereof. When I first joined this agency, another manager overheard me laughing and joking in Spanish with a Cuban immigrant, and this manager passed by looking at me and smiling seemingly pleased that the organization has one more bilingual person to work with many of their monolingual, Spanish-speaking clients. In fact, many of my colleagues to this day think I'm fluent, and there was nothing I can say to convince them otherwise.

In my most recent job interview (as of this writing), the contract manager asked me point blank if I am fluent in Spanish. Like other employers who ask this question, this is what I explained; I speak enough Spanish to have traveled to nine Spanish-speaking countries where I socialized, conducted personal business, and explored new cultures with no opportunity whatsoever to fall back on my English if I happened to get stuck in translation. Fortunately when I'm in a Spanish-speaking country, my level of fluency seemingly rises by default. On the job, however, I've conducted counseling sessions, wrote résumés in English for clients who dictated their experience and skills sets to me in Spanish, and even taught a couple of job search workshops in Spanish, which for me, was a challenge and a stretch.

You might ask, why is it that I feel that I'm not fluent in Spanish? Just ask all of the Spanish-speaking friends I made in the countries I've visited. They will all tell you, oh, Guillermo's (Bill's) Spanish is aiight (it's OK), but certainly not fluent. I'm still working on that!

Monday, May 20, 2013

For Blacks in Cuba, The Revolution Hasn't Begun

I had the opportunity to visit Cuba (legally) back in 1998 to take a Spanish-language intensive course at the University of Havana, but was not there long enough to notice the apartheid type policies that were in place because I was protected by my US passport and dollars. At that time, US currency coveted by Cuban businesses for circulation. We foreigners from everywhere were having the time of our lives, totally oblivious of so many naturalized Cuban citizens risking their lives to escape and seek asylum in places, like the US, Spain, Mexico, and Perú.

My Afro-Cuban neighbor here in Oakland, CA, connected me with his family in Havana, but never explained to me why he himself faced the perils of the waters to escape Cuba on top of an inner tube of a tire. None of his friends whom I also befriended ever complained or reprimanded me for visiting Cuba, like so many other Cuban refugees who left Cuba long before them.

--W Bill Smith

By Roberto Zurbano, editor and publisher of La Casa de las

Américas (House of the Americas) publishing house. This essay was translated by Kristina Cordero

from the Spanish.

CHANGE is the latest news to come out of Cuba,

though for Afro-Cubans like myself, this is more dream than reality.

Over the last decade, scores of ridiculous prohibitions for Cubans

living on the island have been eliminated, among them sleeping at a

hotel, buying a cellphone, selling a house or car and traveling abroad.

These gestures have been celebrated as signs of openness and reform,

though they are really nothing more than efforts to make life more

normal. And the reality is that in Cuba, your experience of these

changes depends on your skin color.

The private sector in Cuba now enjoys a certain degree of economic

liberation, but blacks are not well positioned to take advantage of it.

We inherited more than three centuries of slavery during the Spanish

colonial era. Racial exclusion continued after Cuba became independent

in 1902, and a half century of revolution since 1959 has been unable to

overcome it.

In the early 1990s, after the cold war ended, Fidel Castro embarked on

economic reforms that his brother and successor, Raúl, continues to

pursue. Cuba had lost its greatest benefactor, the Soviet Union, and

plunged into a deep recession that came to be known as the “Special

Period.” There were frequent blackouts. Public transportation hardly

functioned. Food was scarce. To stem unrest, the government ordered the

economy split into two sectors: one for private businesses and

foreign-oriented enterprises, which were essentially permitted to trade

in United States dollars, and the other, the continuation of the old

socialist order, built on government jobs that pay an average of $20 a

month.

It’s true that Cubans still have a strong safety net: most do not pay

rent, and education and health care are free. But the economic

divergence created two contrasting realities that persist today. The

first is that of white Cubans, who have leveraged their resources to

enter the new market-driven economy and reap the benefits of a

supposedly more open socialism. The other reality is that of the black

plurality, which witnessed the demise of the socialist utopia from the

island’s least comfortable quarters.

Most remittances from abroad — mainly the Miami area, the nerve center

of the mostly white exile community — go to white Cubans. They tend to

live in more upscale houses, which can easily be converted into

restaurants or bed-and-breakfasts — the most common kind of private

business in Cuba. Black Cubans have less property and money, and also

have to contend with pervasive racism. Not long ago it was common for

hotel managers, for example, to hire only white staff members, so as not

to offend the supposed sensibilities of their European clientele.

That type of blatant racism has become less socially acceptable, but

blacks are still woefully underrepresented in tourism — probably the

economy’s most lucrative sector — and are far less likely than whites to

own their own businesses. Raúl Castro

has recognized the persistence of racism and has been successful in

some areas (there are more black teachers and representatives in the

National Assembly), but much remains to be done to address the

structural inequality and racial prejudice that continue to exclude

Afro-Cubans from the benefits of liberalization.

Racism in Cuba has been concealed and reinforced in part because it

isn’t talked about. The government hasn’t allowed racial prejudice to be

debated or confronted politically or culturally, often pretending

instead as though it didn’t exist. Before 1990, black Cubans suffered a

paralysis of economic mobility while, paradoxically, the government

decreed the end of racism in speeches and publications. To question the

extent of racial progress was tantamount to a counterrevolutionary act.

This made it almost impossible to point out the obvious: racism is alive

and well.

If the 1960s, the first decade after the revolution, signified

opportunity for all, the decades that followed demonstrated that not

everyone was able to have access to and benefit from those

opportunities. It’s true that the 1980s produced a generation of black

professionals, like doctors and teachers, but these gains were

diminished in the 1990s as blacks were excluded from lucrative sectors

like hospitality. Now in the 21st century, it has become all too

apparent that the black population is underrepresented at universities

and in spheres of economic and political power, and overrepresented in

the underground economy, in the criminal sphere and in marginal

neighborhoods.

Raúl Castro has announced

that he will step down from the presidency in 2018. It is my hope that

by then, the antiracist movement in Cuba will have grown, both legally

and logistically, so that it might bring about solutions that have for

so long been promised, and awaited, by black Cubans.

An important first step would be to finally get an accurate official

count of Afro-Cubans. The black population in Cuba is far larger than

the spurious numbers of the most recent censuses. The number of blacks

on the street undermines, in the most obvious way, the numerical fraud

that puts us at less than one-fifth of the population. Many people

forget that in Cuba, a drop of white blood can — if only on paper — make

a mestizo, or white person, out of someone who in social reality falls

into neither of those categories. Here, the nuances governing skin color

are a tragicomedy that hides longstanding racial conflicts.

The end of the Castros’ rule will mean an end to an era in Cuban

politics. It is unrealistic to hope for a black president, given the

insufficient racial consciousness on the island. But by the time Raúl

Castro leaves office, Cuba will be a very different place. We can only

hope that women, blacks and young people will be able to help guide the

nation toward greater equality of opportunity and the achievement of

full citizenship for Cubans of all colors.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

A Little Taste of Caracas

I've always wanted to visit Venezuela after reading the book entitled Africa in Venezuela by Jesus “Chucho” Garcia. As many African-Americans know, Carter G Woodson is the father of Black history in the US. Well, Jesus García is the father of Black history in Venezuela. My opportunity to visit Venezuela came in December of 2011. However, as I was planning my trip, my co-worker León who is from

Venezuela's notorious capital city of Caracas, discouraged me from going saying

that it is too dangerous. I explained to León that I wanted to spend

my vacation in the Region of Barlovento, the hub of Afro-Venezuelan

culture, and not Caracas. León insisted that every corner of Venezuela

is dangerous. I asked him that if I could pass as a poor, unemployed, Black Venezuelan would that make

me safer? He laughed and said no, thugs do not discriminate when choosing their victims!

Felix, a Venezuelan friend and guide

I met on couchsurfing.com

María, a Venezuelan friend and guide

I met on couchsurfing.com

There was Felix who picked me up at the airport and showed me around Caracas before taking me home to meet and dine with his family and fiancee, and gave me a free place to sleep for the night. He also made arrangements for me to change my American dollars into two times the normal exchange rate giving me far more spending power during my five days in the country. Knowing that I wanted to go to Barlovento, the hub of Afro-Venezuelan culture, he texted María, another person whom I met on couchsurfing.com who has family in that area, and turned me over to her the next day. María herself took me around town as we wined and dined before finally taking me to the biggest and 'baddest' hood in all of Caracas, Barrio Petare. This was the place to catch my bus to Venezuela's Region of Barlovento.

Caracas, Venezuela

All in all, I spent a total of three days in Caracas and found everyone I encountered to be cordial and helpful. I did not come close to experiencing or even observing any of the dangers I heard and read so much about. Sure, I met some slick hustlers, but after having grown up in New York City, that didn't phase me. At the airport, where I was warned to be careful, I got burned for about $30 American dollars by some sweet looking men and women roaming the airport selling CDs of Venezuelan music of which I purchased as souvenirs before catching my flight out. When I got home, I learned that those CDs were either blank or of very poor quality. León, however, was so happy that I made it back to work alive and in one piece. He was pleasantly surprised and delighted that I had such a wonderful and memorable time. My little taste of Caracas was truly an answer to prayer.

Monday, May 13, 2013

My Faraway Latin-American Mother

Mamá Adelina Ballumbrosio

After my very first visit to El Carmen, Perú, Adelina told me that if I ever come back that I will have a family, and she meant every word of it. When I call to say hello, she refers to me as hijo or mijo (son or my son). One year, I got very ill and ended up in a Peruvian hospital. When I got out she and her daughters helped to nurse me back to the strength where I can continue my travels. As an honorary son of hers, I do wire money from time to time, especially on her birthday. However, when mothers day came around. I had to call her and wish her Feliz (Happy) Día de las Madres.

Friday, May 10, 2013

My Spanish Harlem Influence

New York's East Harlem, where Spanish Harlem is located

However, Myrna, a former co-worker who comes directly from Puerto Rico emphasized to me strongly with a pointed finger that I sound more like a “Nuyorican,” that is, a New York Puerto Rican. I was in a recent phone conversation with Jenny, an old college classmate from New York's Lower East Side who herself happens to be Nuyorican. After she heard a bit of my Spanish, she too told me that I sound just like somebody from uptown. In New York City lingo, that means that I sound like someone from Harlem; more specifically, Spanish Harlem. She was right on point because I grew up on the border line of East and West Harlem, and walking distance from Spanish Harlem, which at that time contained a huge Puerto Rican population.

In elementary school, I used to hang out at my best friend's house, Carlos, also a Nuyorican, where every day I would practice my Spanish with his family. His mother even invited me to her church in Spanish Harlem so I can be around more Spanish-speakers. At the age of 16, I started getting into Latin music, specifically the commercialized Latin Soul Music by musicians such as Joe Cuba, Pete Rodriguez, and Joe Bataan, and eventually got into deeper Latin music with such artists as Ray Barretto, Eddie Palmieri, and Willie Colón of whom all, with the exception of Joe Bataan, are Nuyoricans. Joe Bataan himself is half Filipino and half African-American, but grew up in New York's Spanish Harlem.

A Taste of Latin Soul

by Pete Rodriguez

(Don't forget to click “Skip” on the dumb ad)

Monday, May 6, 2013

May is Black Heritage Month in Colombia, South America

The US celebrates African Heritage in February, as does Perú. Ecuadorians celebrate African Heritage in October, and in Colombia, they celebrate African heritage in the month of May. In the year 2000, Colombia's black civil rights (or human rights) movement came up with the month of May as Afro-Colombian Heritage Month to plant seeds in the hearts of the Black community and spark a consciousness with pride in their identity; it's past and present with a focus on the struggles for civil and human rights. Cali, the Afro-Colombian capital offers social gatherings, music performances, fashion shows, Afro-Colombian cuisine, and artifacts to commemorate this event.

Historically, since the 16th century, Africans were being imported into Colombia steadily to replace the rapidly declining native population to work in gold mines, on sugar cane plantations, cattle ranches, and large haciendas. Slavery in Colombia was finally abolished in1851, and even after emancipation, the life of African-Colombians was very difficult due to racism and discrimination. Blacks were forced to live in jungle areas for self-protection and developed harmonious relationships with the indigenous peoples. Since 1851, the Colombian government began promoting mestizaje, i.e., the whitening of the African population to minimize or better yet, eliminate traces of Black African or indigenous heritage. So in order to maintain their cultural traditions, many Africans and Indigenous peoples went deep into the isolated jungles.

In 1945 the department (state/province) of El Chocó was created, being the first predominantly African division in Colombia giving Blacks the possibility of building an African territorial identity and some autonomous decision-making power. However, in the 1970s, there was a major influx of Afro Colombians into the urban areas in search of greater economic and social opportunities for their children. This led to an increase in the number of urban poor in the marginal areas of big cities like Cali, Medellín and Bogotá.

Black Colombians make up 21% of their country's population ranging from 4.4 to as high as 10.5 million, if you count the one-drop rule, making Blacks in Colombia the third largest Black population in the Western world behind Brazil and the US. Most Afro-Colombians are concentrated on the northwest Caribbean coast and the Pacific coast.

African-Colombians have played a role in contributing to the development of certain aspects of Colombian culture. For example, several of Colombia's musical genres, such as Cumbia, Champeta, Salsa, and Vallenato, which like the African-American blues,. have African origins or influences.

Famous Afro-Colombians

The late Jairo Varela

Leader of the world's famous Salsa Band... Grupo Niche

Piedad Cordoba

Columbia's First Black Senator

Colombia's First Black Army General

Former World Middleweight Boxing Champion

African slave liberator who defeated the Spanish over 200 years before the rest of Colombia won their interdependence.

African slave liberator who defeated the Spanish over 200 years before the rest of Colombia won their interdependence.

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Travel Snobbery

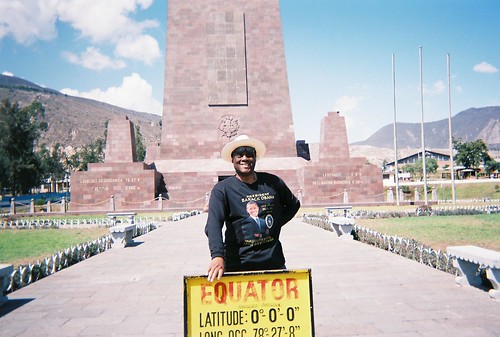

My visit to the equator here in Ecuador is only one of

the few tourist destinations that attracted my attention.

the few tourist destinations that attracted my attention.

In one of my trips to Lima, Perú, I did something that I felt was unforgivable. I stopped in the Lima Hilton Hotel to have breakfast because it was 7am and no other place was open. You might ask, what's wrong with that? Well, when I travel, especially to a Latin-American country, I want to live, breath, and function like a local citizen, and not as a tourist. I want to go, as the expression goes, off the beaten path, and my inadvertent entry into the Hilton was tampering with the whole purpose of my trip.

This brings to mind a blog I recently read entitled Why the Term “Off-the Beaten Path” Annoys Me. Unlike I, who traveled to 14 countries in three continents, the writer herself traveled to more than 60 countries in six continents, and says: whenever I hear or see the phrase “off the beaten path” it makes me grit my teeth just a little bit. The writer expressed utter annoyance at the snobbery and pretentiousness of travelers, who as she puts it, think they are better than others or have had more “authentic” experiences because they’ve gone where not many have gone before. She has even heard such travelers knock other travelers for going on cruises, coach tours, and resort vacations, and I had a good laugh when she added that she has seen them scorn those who go to the Bahamas instead of Burma or Bhutan.

In Perú, I stayed deep in “the hood,” and was treated to live Afro-Peruvian dance performances.

This brings to mind a blog I recently read entitled Why the Term “Off-the Beaten Path” Annoys Me. Unlike I, who traveled to 14 countries in three continents, the writer herself traveled to more than 60 countries in six continents, and says: whenever I hear or see the phrase “off the beaten path” it makes me grit my teeth just a little bit. The writer expressed utter annoyance at the snobbery and pretentiousness of travelers, who as she puts it, think they are better than others or have had more “authentic” experiences because they’ve gone where not many have gone before. She has even heard such travelers knock other travelers for going on cruises, coach tours, and resort vacations, and I had a good laugh when she added that she has seen them scorn those who go to the Bahamas instead of Burma or Bhutan.

In Venezuela, my destination of choice was in the Barlovento region, the hub of Afro-Venezuelan culture.

While laughing, I thought her words were so well spoken that I had to take a good look at myself, because I felt that I might be guilty of the snobbery that she was addressing. I am one who travel with a strict preference for total immersion into the country's culture and lifestyle, and in a Spanish-speaking country, I generally avoid the company of English speakers for the sole purpose of improving my Spanish. Even when I served overseas in the US Navy, I often avoided the company of fellow navy personnel and ventured among the locals.

Instead of a fancy hotel, in the touristy section of Cartagena, Colombia,

I preferred the Getsamane District away from the tourist traps.

I preferred the Getsamane District away from the tourist traps.

In my personal interactions with travelers who enjoy the beaten path, I do remind myself to be nice and show some respect because travel preference is a personal matter. After all, none of the travelers I've met ever dissed me, at least openly, for traveling and staying in the hood where I'm saving a bundle of money; money that can be used for goods and activities that are a lot more fun than, in my opinion, staying in an expensive hotel, or paying high fees for a professional tour guide when I could hire a struggling local citizen who is struggling to make ends meet, and would gladly except a more economical rate. Therefore, even though I'm outspoken about my own travel style, I refrain from openly demonstrating snobbery towards the travel style of others.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)