It was October 2005, in the sleepy, folkloric town of El Carmen, known as the hub of Afro-Peruvian culture where one warm evening, while alone in the living room working on my laptop, a three-year-old girl wandered in from next door. As she so eagerly accepted some sugarless candy I offered her, and as she so sweetly told me her name, Daniela, I felt a strong sense of connection with a little girl who seemed to simply wanted to be loved by a father figure. From that moment, Daniela held a very special place in my heart.

Daniela at age 7 and me

It was so easy for me to slip into Daniela's shoes who doesn't have her father around because I know the feeling of not having my mother around when I was her age. What a divine delight for me to refer to Daniela as mija (my daughter). I don't know where her real father is, but I felt really good inside to learn that Daniela felt this way about me.

I promised Daniela (age 8) a brand new bicycle if she does well in school.

Upon my return to Perú, it was bonding time for Daniela and me. I even brought gifts, but they were no match for the vital gift of a father/daughter relationship. I had a taste of joy reading storybooks to Daniela, teaching her to tell time, taking her and her friends out for ice cream and chicken dinners and to parks and playgrounds. And it was a taste of joy hearing them scream with excitement.

With Daniela's older sister, Ruth (17), being some sort of a chaperon making sure that I'm not one of those—weirdos— who prey on children, I always try to find creative ways to educate and enrich Daniela's life. I teach her a little English and basic computer skills. I have even drilled her on her math, and taught her to play Scrabble, Monopoly, and Chess.

I really feel that Daniela's family is fond of me, but I also feel that they see me as a source of American income. A Peruvian American who himself gets the gringo treatment when he is in Perú once told me that the reason so many Peruvians show me a lot of love is for the money. “It's about the benjamens, moron,” he would insist out of frustration.

Sometimes the family would have Daniela lie about her personal needs to get me to send money. There were times I'd wire money just because, and at other times, I'd decline with an excuse of my own. I also got disgusted by the fact that all the gifts I've bought for Daniela, like bicycles, were sold to bring revenue to the family.

Daniela graduating from primary

school at the age of 12

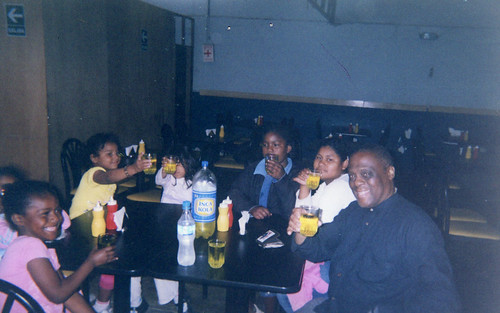

Daniela (far left in pink), and her family members and

I are getting ready to chow down on some grilled chicken.

Today,

the

rapport that I have with Daniela is not as close as before. On my last

trip, the excitement I used to experience from her was no longer there, although I could still see

such excitement in her eyes. I don't know if she is just getting older

and more

reserved like her older sister, or is her family planting seeds

reminding her that I am not family, only a gringo with a pocket full of money. I simply do not know for sure.

Meanwhile, I still feel unconditional love for Daniela. When I return, I want to teach her

pre-algebra and some more English. When she turns 15, I want to sponsor her Quiceañera (equivalent to a sweet 16 party). I'm very happy and

honored to be that male figure to fill the void that Daniela needs in

her life. I love her as though she were my own daughter, and I often

tell her yo te amo, mija (my daughter, I love you).

Daniela (far left in pink), and her family members and

I are getting ready to chow down on some grilled chicken.

%2Bof%2B4886603289_8a3a00cd86.jpg)