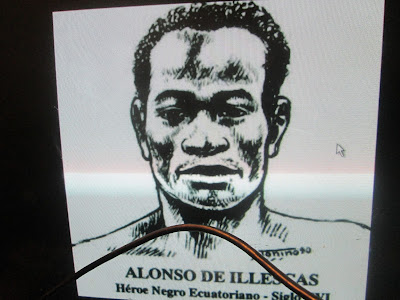

Slave revolt leader Alonso de Illescas was perceived as the single most powerful person in the predominately black Esmeraldas region of Ecuador, South America in the 16th century.

The interesting thing about the African diaspora is that there has always been a few, like Malcolm X (USA), Marcus Garvey (Jamaica), and Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), who are culturally aware enough to recognize and respect those who are fellow members of the diaspora, regardless of language or cultural differences. In most instances; however, too many blacks in varying cultures, including black Americans, cannot see past their own culture, and understand that a black person from another culture shares the same roots, history, and the effects of racism.

In some of my other blog posts, I've addressed attitudes that some Afro-Latinos have towards black Americans even to the degree of denying their own blackness to avoid being identified with us. This is primarily due to the lack of awareness of their own history as well as ours. And I have to say that the same holds true for many black Americans and their attitudes towards other members of the African diaspora.

I once had a good laugh in my office when a black American woman asked me if I were black. I am thinking to myself, what else could I possibly be? My response to her was, “when I looked in the mirror this morning, I was black as always; why do you ask?” Her blunt response; “because you got all this Latin sh... (expletive!) on your wall!” She was referring to pictures reflecting my trips through “Black” Latin America.

Living in California where there is a small Afro-Latino population, I could partially understand this woman's naivete; as hilarious as it was, but in a city like New York with a large representation of Afro-Latinos, it is totally baffling, if not disappointing, to hear that there are black American New Yorkers who also do not seem to know any better.

A tri-lingual (Spanish, English, and Garífuna) friend, Mariana, from Honduras, Central America whom I admire and respect, tells me her story:

Puerto Ricans and Dominicans always assume I'm African American because of my New York/American accent, but once they realize that I am Latina, I am accepted right away.Mariana happens to be a descendant of African people who successfully fought off the British trying to enslave them before taking refuge among the indigenous population; mainly in Honduras, but also in Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, and developed a distinctive language called Garífuna in addition to Spanish.

African-Americans, however; have always denied me my Blackness saying Black people don't speak Spanish. They, too, have been denied the education of the transatlantic slave trade.

Growing up in a black (American) neighborhood in Brooklyn, the confusion among my friends didn't come until my mother yelled at me in Spanish because I stayed out so late. Instead of my black American friends making fun of me, they questioned me with "I thought you were Black?"The interesting thing I learned from my travels through “Black” Latin America is that they know much more about us black Americans than we, as a whole, know about them. They know about hip hop, jazz, R&B, and gospel. In fact, it was an Afro-Peruvian woman who turned me on to a black American folksinger whom I never heard. Yet, hardly any of us black Americans know about punta (Honduras), rumba (Cuba), marimba (Ecuador), or festejo (Perú)—all “black” music.

What the American history books does not teach us is that slave ships began docking in Latin-American countries in the 1500s, almost a full century before before they started docking in the U.S. For this reason, Spanish-speaking black folks in the Americas far outnumber us English-speaking black folks.

I have personally met Central Americans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and heck, even Peruvians (yes, Peruvians!) who are closer to their African roots than most African Americans. So, who are we to judge Afro-Latinos as being anything other than black?

Furthermore, what American slave rebels like Nat Turner and Denmark Vessey attempted to do before being ratted out by house negroes, Gaspar Yanga of Mexico, Benko Biohó of Colombia, and Alonso Illescas of Ecuador, and so many others, were successful in terms of winning their freedom and creating palenques (fortresses) for protection. A black woman in Ecuador won her freedom by taking her slave master to court.

Although I am a proud black American considering our history, struggles, and accomplishments, too many of us feel that we are the only legitimate black folks on the planet, when in essence, we are just a mere minority. A black Venezuelan living in Washington DC made that point very clear out of frustration in one of our recent discussions.

We, as a community, as well as blacks around the world, need to learn to recognize and respect other members of the African diaspora, especially those who are also descendants of slaves in the Western world. Collectively, we speak Creole, Dutch, English, French, Garífuna, Gullah, Patois, Portuguese, and Spanish.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Anonymous comments will be ignored and deleted.